JAKE HANCOCK, GEOLOGIST AND WINE RESEARCHER

John Michael Hancock, who died on the 4th March 2004 after a short illness, was the world’s most widely known and popular Cretaceous geologist. Jake Hancock was born in 1928 in Salisbury and attended Dauntsey’s School, where he demonstrated a precocious knowledge of science by giving a talk on the construction of an atomic bomb, then entirely top secret information. After working as a wireless mechanic for the RAF in the Middle East (1947-49), he went to Queen’s College, Cambridge (1949-52). He stayed at Cambridge to undertake a PhD supervised by Maurice Black on marginal (shallow water) facies of the British Chalk (1952-55). His fieldwork took him both to Northern Ireland and western France by bicycle, which rather curtailed his fossil collecting. In Cambridge he roomed with an aged palaeontologist, Gertie Ellis, who strongly approved of the fact that Jake brought fossils home to clean on her sitting room carpet. In 1955, he was appointed to an Assistant Lectureship at the Geology Department, King’s College, London. He obtained his PhD in 1957, and progressed to obtain first a full lectureship, then a readership in 1977. Closure of the King’s College Geology Department briefly interrupted his career, but in 1986 he was given a Chair at Imperial College, where he stayed and continued to teach well beyond his retirement. Even though he lived most of his life in London, Jake remained in many ways a countryman, with extensive interests in gardening and agriculture, and a superb collection of rare seed potatoes.

Jake’s geological research work included important contributions to several discrete areas. As a stratigrapher investigating Cretaceous rocks, he realised the fantastic value of the detailed study of fossil ammonites in making precise correlations (drawing lines approximating to time) between countries and continents, and he developed these correlations in numerous papers, especially working with his former student Jim Kennedy. Jake argued that ancient global sea-level changes could be identified and correlated long before the Exxon sequence stratigraphy group made this popular in the 1980s. Thirdly, his studies on the sedimentology of chalk were to prove of fundamental importance in the discovery and development of oil reservoirs in the Chalk of the North Sea. Jake worked extensively with the petroleum industry on the investigation of chalk reservoirs. The high quality of his work was acknowledged by his receipt of the Lyell Medal in 1989, one of the highest awards of the Geological Society of London and the Chair at Imperial College. An exchange year in Washington in 1971 allowed Jake to travel widely and develop his abiding love of the USA, its people and history. He had many close friends in the United States, whom he visited regularly.

His interest in wine developed alongside work on the Cretaceous rocks of France. By sheer good luck, three major wine producing regions, the Loire, Champagne and Bordeaux either sit upon or are adjacent to Cretaceous rocks. These are not just any Cretaceous rocks, but include the standard global reference sections where periods of Cretaceous time were originally defined (e.g. Coniacian after Cognac in Charente). Fieldwork in these districts is naturally accompanied by a certain amount of wine tasting, and over the years Jake obtained an exceptional knowledge of French wines in particular. This subsequently grew into a scientific study of the geological and climatic factors which control production and quality of wine, and he was invited to lecture upon the professional Master of Wine course. Latterly, he was to become an editor of the Journal of Wine Research, and Jake wrote and lectured widely about the relationship between geology and wine. He raged particularly against the French concept of terroir (the idea that geological and climatic characteristics of a district impart unique flavours to a product grown there) which he saw as mostly superstition and pseudoscience.

His interest in wine developed alongside work on the Cretaceous rocks of France. By sheer good luck, three major wine producing regions, the Loire, Champagne and Bordeaux either sit upon or are adjacent to Cretaceous rocks. These are not just any Cretaceous rocks, but include the standard global reference sections where periods of Cretaceous time were originally defined (e.g. Coniacian after Cognac in Charente). Fieldwork in these districts is naturally accompanied by a certain amount of wine tasting, and over the years Jake obtained an exceptional knowledge of French wines in particular. This subsequently grew into a scientific study of the geological and climatic factors which control production and quality of wine, and he was invited to lecture upon the professional Master of Wine course. Latterly, he was to become an editor of the Journal of Wine Research, and Jake wrote and lectured widely about the relationship between geology and wine. He raged particularly against the French concept of terroir (the idea that geological and climatic characteristics of a district impart unique flavours to a product grown there) which he saw as mostly superstition and pseudoscience.

Jake was one of the great characters of the UK geological community, with long white hair and an extraordinary laugh; this began well below the diaphragm and progressed upwards as a series of seemingly uncontrollable paroxysms, before escaping at incredible volume as huge guffaws. It was able to silence a room full of eagerly chatting and drinking geologists. A further miraculous gift was his ability to sleep, sometimes noisily, through the entire delivery of a scientific talk, then awake at the end to ask the most pertinent, incisive question.

Jake was a generous, kindly and unpretentious man with an exceptional intellect, and a very broad knowledge of both sciences and arts. He gave freely of his time to help many scientific societies, and scientists from diverse countries. He taught science and mathematics at the London Working Men’s College and later sat on its governing body. His sharp financial acumen greatly benefited the various societies for whom he was treasurer. He was truly an exceptional person, greatly loved by his numerous friends from many countries and diverse walks of life. He is survived by Ray Parish, his partner of 42 years.

Andy Gale

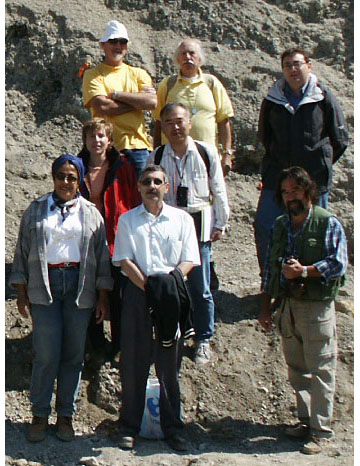

Jake Hancock, in the middle of the last line, with other participants in the Cantera de Margas, Olazagutia, on 14th September 2002,

during the Meeting on the Coniacian-Santonian Boundary. Bilbao, Spain.

His interest in wine developed alongside work on the Cretaceous rocks of France. By sheer good luck, three major wine producing regions, the Loire, Champagne and Bordeaux either sit upon or are adjacent to Cretaceous rocks. These are not just any Cretaceous rocks, but include the standard global reference sections where periods of Cretaceous time were originally defined (e.g. Coniacian after Cognac in Charente). Fieldwork in these districts is naturally accompanied by a certain amount of wine tasting, and over the years Jake obtained an exceptional knowledge of French wines in particular. This subsequently grew into a scientific study of the geological and climatic factors which control production and quality of wine, and he was invited to lecture upon the professional Master of Wine course. Latterly, he was to become an editor of the Journal of Wine Research, and Jake wrote and lectured widely about the relationship between geology and wine. He raged particularly against the French concept of terroir (the idea that geological and climatic characteristics of a district impart unique flavours to a product grown there) which he saw as mostly superstition and pseudoscience.

His interest in wine developed alongside work on the Cretaceous rocks of France. By sheer good luck, three major wine producing regions, the Loire, Champagne and Bordeaux either sit upon or are adjacent to Cretaceous rocks. These are not just any Cretaceous rocks, but include the standard global reference sections where periods of Cretaceous time were originally defined (e.g. Coniacian after Cognac in Charente). Fieldwork in these districts is naturally accompanied by a certain amount of wine tasting, and over the years Jake obtained an exceptional knowledge of French wines in particular. This subsequently grew into a scientific study of the geological and climatic factors which control production and quality of wine, and he was invited to lecture upon the professional Master of Wine course. Latterly, he was to become an editor of the Journal of Wine Research, and Jake wrote and lectured widely about the relationship between geology and wine. He raged particularly against the French concept of terroir (the idea that geological and climatic characteristics of a district impart unique flavours to a product grown there) which he saw as mostly superstition and pseudoscience.